British-born architectural critic/historian Reyner Banham [1922-88] is perhaps the greatest interpreter of the city of Los Angeles -- how it happened and what makes it tick. His writings about the place, and especially his short film Reyner Banham Loves Los Angeles [1972] deconstruct the city as no one else has done before or since.

I love L.A. almost as much as Banham, and find it an incredible garden of earthly delights with a rich, unexpected array of resources. It's also completely out of control and over the top. I visited in simpler times -- 1976, 1982 and 1985 and not since. It's not everybody's cup of tea. [Mike Davis's book, City of Quartz offers a useful perspective of modern-day L.A. as it has developed in the years after Banham's passing.]

In the early 1930s quite a few show business actors, producers, writers and crewpersons relocated to Los Angeles from New York, as Hollywood became the headquarters for motion picture production. In the book Grocuho, Chico, Harpo and Sometimes Zeppo, a Marx Brothers bio by Joe Adamson, the author recounts a cross-country trip by S.J. Perelman and Will Johnstone, comedy sketch writers for the Marxes:

"Now we cut back to Hollywood, where Perelman, thoroughly appalled all the way across the country by his prolific partner [Johnstone insisted on doing watercolors of every vista that came into view, besides getting three weeks of comic strips finished in three days, all with a hand shaken by a rocky roadbed and three crocks of illegal applejack], now stepped off the train to be appalled anew, by what he later described as a land of "Moorish confectionaries, viscid malted milks, avocado salads, frosted papayas, sneak previews... studio technicians, old ladies studying Bahaism, bit players, chippies, upraised voices extolling the virtues of various faith healers or laxatives... the city of dreadful day... Bridgeport with palms... a metropolis made up of innumerable Midwestern hamlets... an unalloyed horror... a hayseed's idea of the Big Apple... everything about that city's murders had the two-dimensional quality of American life... viewed in full sunlight, its tawdriness is unspeakable; in the torrential downpour of the rainy season, as we first saw it, it inspired anguish... After a few days I could have sworn that our faces began to take on the hue of Kodachromes, and even the dog, an animal used to bizarre surroundings, developed a strange, off-register look, as if he were badly printed in overlapping colors."

Perelman didn't get it. Banham did. In England and elsewhere Banham used to cut a sporting figure [tall man with a neat suit and bushy beard] riding a folding bicycle. He learned how to drive later in life when living in L.A. so he could understand the area better. In his 1971 book Los Angeles: the Architecture of Four Ecologies he breaks down the area's experience by geographical overlays, and in so doing deepens our understanding of its unique cross-cultural mashup and novel aspects.

Also really enjoyed his 1982 book Scenes in America Deserta. This one is out of print and hard to find, but worth it. Banham uses his investigative and analytical triangulation to cast a wider net over the wide open spaces of the American West.

There is also a 2003 biography of Banham called Reyner Banham: Historian of the Immediate Future, by Nigel Whiteley. It's a lengthy volume with lots of photos and graphics collected, and ultimately runs a little flat and isn't nearly as interesting as its subject.

Banham has the qualities I like the most in writers and documentary producers: an infectious enthusiasm and strong sense of humor and the absurd.

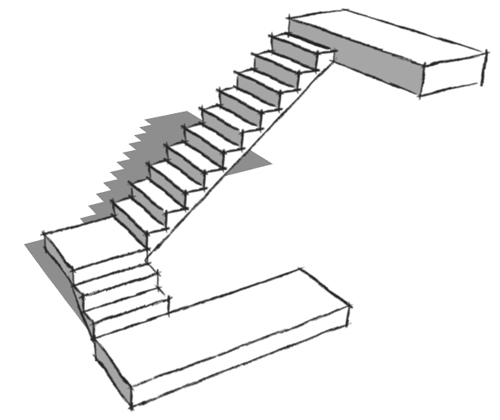

![Cross-section of Forever House [one of FRamE Featured Projects on this site]. Drawing shows stairs [dashed in, beyond] and their placement to connect the interlocking half levels of the house. A variation of switchback stair type.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5771e6b1f5e2314b4833ec6d/1471139169418-WZR6VSMCLM16D4PDO649/image-asset.jpeg)

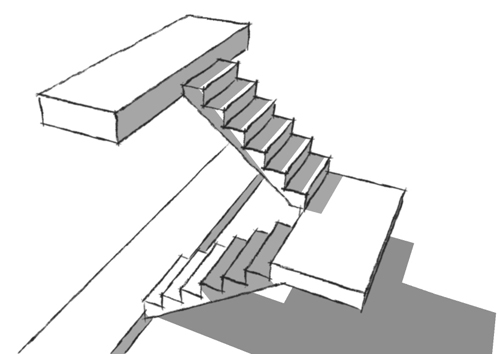

![Stairs in a tri-level. Basement [about three feet below grade] on left, crawl space below mid-level on right. The area left over under the stairs isn't as much of an issue.](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5771e6b1f5e2314b4833ec6d/1471134691805-5XUGE6YAQFCCOET9258L/image-asset.jpeg)